Among the reforms planned by government is the introduction of an independent regulator to oversee the water sector. From Moneyweb.

As South Africa wrestles to balance its budget and avoid any further tax increases, fixing its leaky water problem poses both a challenge and an opportunity.

The water crisis is no longer a distant threat – it’s here, seeping into farms, homes, and headlines.

Xolani Zwane, deputy director-general of the Department of Water and Sanitation (DWS), says some farmers have quit the business entirely, driven out by water so poor it is unfit for crops or livestock.

With 46% of drinking water systems failing microbiological standards in 2023 – up from 5% in 2014 – and 66% of wastewater infrastructure crumbling, water is the next crisis (after electricity) to face the country.

Read: First power, now water …

Among the reforms the government is banking on is an independent water regulator to police the sector.

The numbers are not encouraging. The 2023 Blue Drop and 2022 Green Drop reports show that 73% of Water Services Authorities (WSAs) scored “critical” or “poor” in water and wastewater management. Non-revenue water – lost to leaks or unpaid bills – jumped from 37% in 2014 to 47% in 2023, meaning nearly half the treated water municipalities produce earns nothing.

“If you’re losing approximately half your potential revenue, it’s very hard to make a profit,” says Shyam Misra, Group MD of South African Water Works (SAWW), speaking last week at a PSG Investing in Water seminar.

His firm slashed water losses in Ballito from over 50% to 12% in a private concession, proving that it is possible if done right.

Public-private partnerships

There are just two full public-private partnerships (PPPs) that encompass the entire water value chain in SA: Siza Water in Ballito, KwaZulu-Natal, and Silulumanzi in Mbombela, Mpumalanga. Both are operated by SAWW, in which Mergence Investment Managers is a key investor.

Both have been in existence since 1999, and they have outperformed their publicly run peers in almost every metric.

The government is finally getting serious about introducing PPPs, similar to what it is doing in Transnet and electricity generation, to avert the looming water crisis. It is now looking at more PPPs, similar to Siza and Silulumanzi, in the water sector.

Under the Water Services Amendment Bill introduced last year, municipalities risk losing their Water System Provider (WSP) licences if they do not demonstrate the minimum competence and capabilities required for the job.

Just 26 out of 958 water supply systems in SA received Blue Drop certification, which grades infrastructure, skills, and monitoring. This gives some notion of the scale of the problem facing the country. Of these 26 water systems, SAWW accounts for five, serving some 500 000 people.

The DWS’s reform plan, turbocharged by Phase 2 of Operation Vulindlela, hinges on structural shifts. Municipal water services are bleeding cash, so the proposal is to ringfence revenues – ensuring that money from water sales funds water fixes, not other council whims.

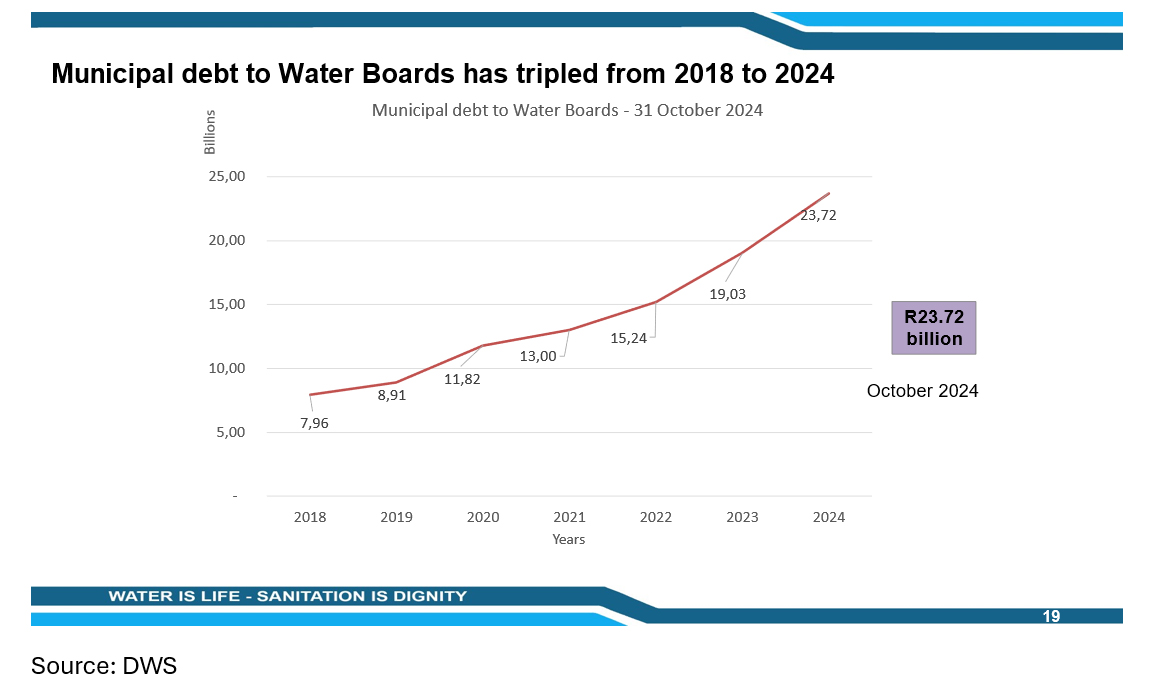

The worst offenders are Gauteng’s metros and Mpumalanga’s rural councils, such as Merafong, which owed R763 million, and Victor Khanye, owing R356 million, per Rand Water’s 2023 tally.

Gauteng’s skilled staff keep the metro afloat, while Northern Cape’s skills shortages have sunk it.

Tech, cash and efficient management

SAWW’s Misra flags tech as a saviour, such as sensors to spot leaks and smart meters to claw back revenue – but rolling that out takes cash and will, both in short supply.

This is where private players shine.

SAWW’s 25-year water concessions show the sector can attract investment and generate decent returns, provided there is sufficient upfront investment to repair and upgrade creaky infrastructure.

These private concessions have a 95% collection rate, far higher than most municipalities, while still supplying limited free water to indigent households.

But as Misra points out, this requires fixing leaks as soon as they appear and keeping other infrastructure in good order.

Chito Siame of Mergence Investment Managers, with a decade of experience in privately run water projects, sees big opportunities for companies and industries to self-provide, just as mines and industrial parks have provided their own solar power units.

Read: State’s R1.3trn infrastructure plans unaffected by budget dispute

Preshan Govinder of the JSE argues that blue bonds, green bonds, and listed equities in a highly regulated environment could fund the next round of water investments, given the government’s new regulatory regime and private sector appetite for stable, long-term investments.

SAWW has shown what is achievable when private players get involved in a sector. The DWS has set up a Water Partnership Office to assist in hunting these funds.

Justice for offenders

But we’re not over the hill yet. “The justice system is slow,” Zwane admits – criminal cases against polluting municipalities drag on for three or four years, and fining 40% of offending water service authorities isn’t a fix; it’s a symptom.

The current funding model is patchwork. The fiscus covers “social” projects – like rural dams – while water boards borrow and repay via sales.

Municipalities get over R60 billion yearly from national grants, but these can’t be used for operations or maintenance, which must come from revenues.

Globally, private water works – sometimes. The UK’s privatised system Thames Water cut leaks but hiked bills; Chile’s concessions slashed non-revenue water to 30% but sparked equity fights. SA’s private push could mirror Ballito’s success – or stumble if licensing reforms lag.

“Changing political climate and capacity constraints are challenges,” Misra cautions, adding that ensuring accountability for poor performance and embracing appropriate tech to the problem can unlock returns.

Can the private sector rescue SA? It’s not a silver bullet – 47% water loss and 90 critical wastewater systems won’t be fixed overnight. But with an independent regulator setting rules, private firms could plug the gaps – funding dams, fixing pipes, and turning losses into gains.

For a country where cholera is back and farmers are fleeing, it’s a lifeline worth betting on. The question is whether politics and pace will let it flow.