Your employment prospects are bleak and government is not coming to rescue you. From Moneyweb.

In 1994, there were 3.7 million unemployed people in SA. Today, that figure stands at 12.6 million – a 240% increase. Contrast this with the 42% growth in the labour force, from 20.6 million to 29.4 million since 2008.

If you’re black and aged between 15 and 24, your chances of employment are less than 40%. This is clearly unsustainable.

What this means is that roughly 1 000 South Africans have joined the unemployment ranks every day for the past 17 years. That’s an abysmal record for an ANC government elected on promises of job creation, transformation, clean governance, and all the other bromides festooning its election posters.

Can it be fixed?

Of course, it can – but it needs a radical change of course.

Just this week, President Cyril Ramaphosa declared an economic emergency and announced a 10-point plan to revive growth and create jobs.

These include using electricity tariffs and transmission investment to drive economic activity, fixing Transnet ports and rail networks, rebuilding the chrome and manganese industries, and improving the state’s capacity to manage large-scale projects.

On top of that, he proposes more funding for public employment programmes and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

This, despite research by the Centre for Development and Enterprise (CDE) showing R6 billion being spent on SMEs over the years, with precious little to show for it.

Public employment programmes do not result in real jobs; they only paper over the problem.

A new report by the CDE lays out the employment problem in stark terms and then offers some easy (and not so easy) fixes.

Scale of the problem

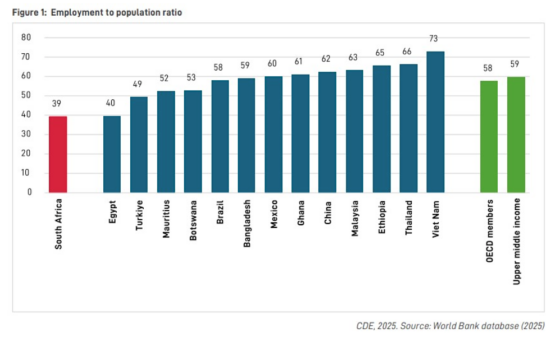

South Africa’s unemployment rate is a global anomaly: fewer than 40% of adults have jobs, which is about 20 percentage points below the norm for upper-middle-income countries

Not only is this shockingly low, it’s getting worse.

Who speaks for the nearly 13 million without jobs?

Remember the National Economic Development and Labour Council, or Nedlac? That was supposed to be the forum bringing government, business, and labour together in a single room to hammer out solutions that would deliver SA from its historical baggage.

Government frequently disregards Nedlac, and it’s questionable whether any of its constituent groupings truly represent the unemployed. If they did, they would take a chainsaw to the regulations strangling job creation. That would require a Margaret Thatcher-scale showdown with the trade unions, something the ANC appears unwilling to do.

Read:

Nedlac fights for relevance and renewal

After a decade of sub 1% growth, maybe it’s time to rethink special economic zone

One way the ANC could get around this is by building alliances in support of Special Economic Zones (SEZs), where firms can set their own working conditions. Organised labour opposes this, seeing SEZs as Trojan horses for the demolition of hard-won workers’ rights.

China and Mauritius kickstarted their economic revivals through SEZs, despite internal opposition. SA could do the same.

In June, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) found SA’s regulatory regime more restrictive than all other OECD countries.

Let that sink in.

In February this year, the World Bank found that SA faces “severe regulatory limitations to competition in key sectors of the economy: with the level of restrictiveness close to three times higher than those in the top-performing countries”.

Senior managers in small businesses spend roughly 11% of their time dealing with regulatory matters, compared to 6.7% in other middle-income countries.

Big business can afford risk and compliance officers to deal with this tangle of red tape, small business cannot.

Unleashing the small business sector, which is the real engine of growth and job creation, would require ripping out all but the most rudimentary regulations.

SA’s employment-to-population ratio (red column)

SA’s informal sector too small

One of the reasons for SA’s weak job creation is, ironically, the surprisingly low number of informal-sector jobs, which includes agriculture.

Think tanks have pored over the reasons for this, such as apartheid’s destruction of small-scale agriculture, residential segregation that suffocated entrepreneurs in low-income areas, and vigorous enforcement of regulations. While other countries tolerate informality, SA tries to rope them into the regulatory and tax net.

It may be that we are undercounting the size of the informal sector, as former Capitec CEO Gerrie Fourie claimed earlier this year, based on analysis of the transactional activity of nearly half the SA population.

Read: Why SA has 32.9% unemployment and Zimbabwe 8%

Small though it is, the informal sector provides employment to around 3.5 million South Africans, about 20% of the country’s total employment.

SA’s ‘anti-growth strategy’

SA has pursued an anti-growth strategy for much of the last 20 years, championed by cabinet members who have never run a business, let alone a key national portfolio.

The CDE report highlights the failures that have stifled growth and job creation: the collapse of state-owned companies such as Eskom and Transnet; a deepening fiscal crisis; high levels of corruption; municipal collapse; and badly conceived and implemented economic transformation and industrial policies.

“Each of these failures on its own would have slowed growth. Together, they have collapsed growth to little more than zero,” says CDE executive director Ann Bernstein.

“And when an economy doesn’t grow, neither does the number of jobs.

“Economic growth is by far the most potent lever for reducing unemployment.”

The CDE estimates that growth of 4% would create 400 000 new jobs every year. That’s a tantalising target that should seize every waking moment of our political class.

What can be done about it?

The CDE offers a few suggestions. Start with the Labour Relations Act. Introduce a 12-month probation period making it easier to dismiss workers other than for unfair reasons such as racial discrimination.

Stop the undemocratic bargaining council agreements being imposed on firms that had no hand in shaping them. These are a kind of cartel arrangement between big business and labour that impose working and pay conditions on all firms in the same sector.

Exempt small, new, and labour-intensive firms from these agreements, and let them run free.

Remove restrictions on labour brokers, whose services help expand opportunities and create entry points for people with no other on-ramp to the labour market.

Fix the skills system by scrapping Sector Education Training Authorities (Setas), which suck 1% of company payrolls while delivering little of value, and instead focus on employer-led apprenticeships and private training geared towards the needs of business.

While we’re about it, overhaul the Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) colleges, which fail to provide young people with the skills that employers require.

Listen/read: Risenga Maluleke’s insights on rising SA unemployment

Let’s find out from small businesses to understand how new and existing regulations affect them, and put any new legislation or regulation to the SME test.

If funding is to be provided, let the private sector fight it out on a competitive basis, with report-backs every few months. May the strongest survive.

Government’s record of funding SMEs is, at best, hard to quantify and, at worst, terrifying. It should simply be made to get out of the way.

There are other things that could be done, such as encouraging city governments to zero-rate licences for street traders, perhaps introducing transport subsidies for informal traders, and start selling off the state’s 2.5 million hectares of land.

The CDE argues that intelligent densification of cities makes more sense than rural economic programmes. Land should be made available for low-cost housing, underpinned by a new housing policy that creates access to housing in dense, economically viable parts of the city.

“South Africa’s institutional environment pushes up the cost of employment and locks millions out of work,” says Bernstein.

“We shouldn’t romanticise the informal economy, but we need to create more space for people to find their own livelihoods.”